Contemporary Garden Design

Jill Weatherhead B Sc Grad Dip L Arch

There’s a couple of ways of looking at a garden: in the traditional English (and generally Australian) way which is purely visual – which works, incidentally, well for flower gardens, billabong gardens and most modern gardens. How does it look? Is it in proportion? Are elements placed well?

A second, fairly new approach (in Australia) to garden enjoyment can be termed Mediterranean-style as described by Canadian-born, French-based Professor Louisa Jones. All the senses are savoured as you move through the garden, not just sight. You might pick a fruit, smell a flower, rub a herb, dip a toe into water, sit to eat, hear birds; you don’t just stand and look although ideally the garden is beautiful as well.

What’s not often enough acknowledged is a third strand underlying some gardens, one I find the most appealing: one that engages the intellect or has an underlying meaning. Some of these gardens I would call `concept gardens’ and I strive for this myself in my country garden with my magnified atom (Carbon of course) and plans for a pergola shaped like DNA (the genetic material at the heart of every cell in the body). (Why? Well, I majored in Biochemistry in my Science degree and it’s just how I see the world…)

Many parts of The Australia Garden at Cranbourne’s Royal Botanic Garden (Victoria) have a deep meaning which make the garden more satisfying to visit. There’s the famous red soil plain and lunettes that remind us of the country’s interior, of course, and the enormous, sheer rust wall representing King’s Canyon. But, importantly, the garden charts the journey of water in this country and my favourite part of the garden involves water…but isn’t widely known. Go to the end of the square rock pools and every 20 minutes or so the water flow slows and stops like a drought has occurred. Wait…and the `drought’ breaks. Water comes towards you slowly, then it rushes then it roars as it reaches the `waterfall’ and tumbles over gently then in a torrent. I am reminded of a farmer’s family dancing in the rain (or so the ads would have us believe) after a drought…I love it.

The garden doesn’t just make you feel; knowing the story makes the garden experience richer.

Just as an artwork has hidden levels, so may a garden. I’ve just seen a bed – of sorts – made of wood. What sort of art is this? But read about it, find that that Chinese artist Al Welwei has constructed the large piece from dismantled temples, to feel a shiver, to ponder the `embedded trauma’ (Robert Nelson, `The Age’). And gardens can certainly aspire to be art.

Some public gardens are expected to have this sort of underlying meaning. Chelsea Flower Show gardens, too, have stories. One I liked from 2010 told the story of a neuro-scientific discovery: that coloured glasses (with blue or yellow lenses) helped some children to learn to read. Half the garden had white flowers, but go through a gate in a wall and the flowers became vividly colourful – in blues and yellows – and there was a giant book on a seat. It was a beautiful little garden; meaningful yet standing alone as a garden that `worked’ (i.e. it was beautiful) should visitors decide to not read the notes telling the underlying story.

With a greater emphasis on artistry (and a little less on horticulture) the months-long garden show at Château de Chaumont in the French Loire Valley each year has about 20 inspiring installations from landscape designers, landscape architects and artists selected internationally and is jam-packed full of ideas. The theme in 2016 is `nature’; the concept gardens never fail to impress.

Go south to Terrasson-Lavilledieu where American landscape architect Kathryn Gustafson created Les Jardins de l’Imaginaire with architect Ian Ritchie at Terrasson Park near Sarlat. Created in 1996, this 6ha (15 acre) public park and contemporary garden uses thirteen tableaux to present the myths and legends of the history of gardens with simple natural elements – trees, flowers, water and stone to suggest the passage of mankind from nature to agriculture to the city and incorporates fountains, cascades, and basins to great effect. An important part of visiting Les Jardins de l’Imaginaire is to discover the narrative and – a big ask – ponder the history of humanity itself.

Back in London is another landscape by Kathryn Gustafson, opened in 2004: the popular Diana, Princess of Wales Memorial `fountain’. The memorial reimagines a water feature into a virtually horizontal fountain, an enormous circular stone stream of water representing the life of the famous princess. With just stone and water, two simple elements, Kathryn Gustafson has designed a landscape – a water sculpture in a simple lawn setting – which displays many sides of the princess’ life with pools and areas of gently flowing water for the peaceful times and rushing and gushing water with air jets in grooves and channels in other parts to represent the turbulent and exciting times.

Or we can just enjoy this landscape architecture – impressive at 80m across – without thinking about a circle of life.

A few private gardens have emerged in the last 30 years or so which buck the trend to be (just) pretty gardens. One such is the Garden of Cosmic Speculation (begun in 1989), a 12 hectare (30 acre) sculpture garden, created by landscape architect and theorist Charles Jencks at his home in south west Scotland. Like much of Jencks’ work, the garden is inspired by science and mathematics including modern cosmology, with sculptures and landscaping (including Jenck’s famous landform landscaping) on these themes, such as DNA, black holes and fractals. I may not, personally, like the steel DNA sculptures, but the other, more attractive elements speak to me strongly. I guess I’m still used to `pretty’ in the garden (or, at least, not seeing bold modern steel structures placed amongst the traditional flower borders).

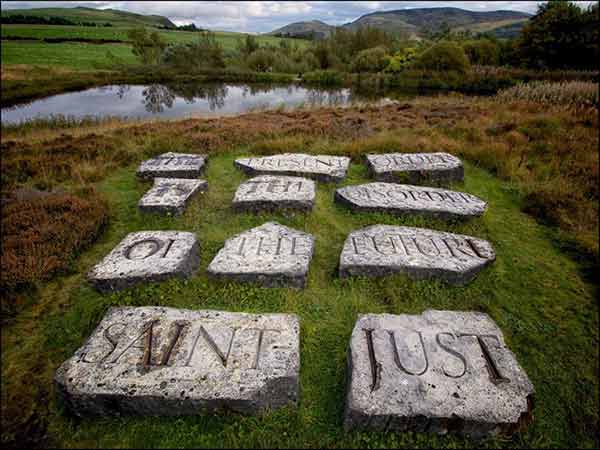

Nearby, and earlier, Ian Hamilton Finlay created `Little Sparta’, deliberately named to be a political statement, an unusual garden, of woodland and meadows peopled with ancient quotations and inscribed stone tablets. It is `implicitly a critique of contemporary cultural values’ says garden critic Tim Richardson. A garden with these classical allusions has more in common with the picturesque gardens of the 18th century than the gardenesque fashion of the Victorians that followed – and British gardens since – where only the plants mattered. I think something important was lost; I’d like to seize it back – and arguably Hamilton Finlay began the movement.

Go south to Gloucestershire and we find Througham Court, where scientist turned landscape architect Dr Christine Facer has created a spectacular 2.4ha (6 acre) garden inspired by scientific facts and theories. `A garden for the 21st century’, it includes the Cosmic Evolution Garden, Fibonacci’s Walk, Chiral Terrace, the Six (Scientific) Pillars of Wisdom and much more. Garden critic Mary Keen writes `Througham Court’s garden seemed to me to be more didactic than atmospheric. It is about explanation rather than exploration’ but I find that exciting; something to be celebrated. Besides, the garden has beauty; one is not forced to understand the underlying meaning – it just makes the journey so much richer and satisfying – as with all art.

Nearby is an exciting new garden created by Alasdair Forbes in Devon. `Plaz Metaxu’ is a 13ha (32 acre) country garden full of sculptural meaning, using stone, lawn, hedges, paving and clever sculpture, like the magnified `Pilcrow’, a `new paragraph’ sign in simple materials along a narrow path. `Pilcrow’ is everything you could want in a garden sculpture: meaning, good placement, and a severe, simple, fantastic beauty.

Head north to Veddw House in Wales to see self proclaimed `bad-tempered gardener’ and garden critic Anne Wareham’s country garden created with photographer Charles Hawes over 25 years. The 0.8 ha (2 acres) garden surrounds a modern reflecting pool amid undulating hedges; further plantings represent surrounding historic farms, deeds and titles based on the Tithe Map of 1842. Colour is used well.

`When, at Veddw in Monmouthshire, Wareham replants the lines of vanished hedgerows with box and fills the enclosed spaces with grasses and hardy perennials, she is linking the land-use of the past with the aesthetic of the lordly parterre.

By giving expression to contemporary sensibility about conservation, she invites intellectual engagement.’ (Garden writer Germaine Greer, The Guardian, June 2007.)

Cross the Atlantic and at the same time we see Martha Schwartz’ groundbreaking landscape architecture and we don’t just see her famous bagel garden, we see arguably her first, real triumph: the balcony outside the gene splicing laboratory where she created a diagonally spliced garden, half French with topiary coming out from the wall, and half Japanese-inspired with astro-turf looking like waves of raked gravel around stones. This was the woman who dared to be different, to bring pop art into the garden, and create concept gardens, and arguably helped gardens be seen as an art form once more.

Sir Geoffrey Jellicoe once said “You should go on thinking about a garden long after you leave it” and I love a garden that makes me think; a garden that aspires to high art. It’s not just daubs of plants here and there. I delight in well-placed plants, oranges and yellows, say, and straw-coloured grasses added for texture, for example, complementing each other beautifully. But it’s been done for a long time now. And let’s face it, Australian Big Boys Boulder gardens aren’t for all of us; nor are the recent green-on-green. Current native and kitchen gardens say `I save water’ and `I reduce food miles’ respectively but often aren’t attractive (and often don’t!). A pity.

Let’s say something! Like my magnified atom. And by the way – it doesn’t just speak of my science background and how I see what makes up the world. (I hope it does that much.) For example: why is my magnified atom a Carbon atom? It’s pondering that we are carbon-based life forms; our mortality. It’s political, too, of course: it says something (or a lot) about my politics, my aims, my hopes. With its 6 `electrons’ evenly spaced I think it looks attractive too. As Germaine Greer says, `Gardening can be – should be – conceptual, which is simply a way of saying that gardens should have ideas in them and the ideas should be perceptible.’

If you are interested in seeing the inspiring garden show at Château de Chaumont in 2017 – a must for landscape designers – and Througham Court, Veddw House, Plaz Metaxu and other Contemporary, Concept and Cutting-Edge Gardens in May and June 2017 join Jill Weatherhead with Halcyon Travel as we move from London (seeing the best contemporary public gardens including an extraordinary landform landscape) to southern Britain (visiting some fabulous private gardens including whimsical Bryansground, one of my favourite gardens, home of editor and illustrator of Hortus, journal of best English horticultural writing) and then to Paris to see Parc de la Villette and Promenade Plantée and other landscapes including Jardin Plume with its modern twist on prairie plantings amid curving and unusually formed hedging) and some wonderful contemporary French gardens (public and private). Warning: some gardens may have flowers.

A tour for landscape designers and lovers of contemporary gardens.

Visit www.halcyontravel.com.au.

Jill Weatherhead is a landscape designer, horticulturist and garden writer in the Dandenong Ranges, Melbourne and surrounds.

Mob: 0407 329 881

Email: j.weatherhead@bigpond.com

Web: www.jillweatherheadgardendesign.com.au

Blog: thegardenatpossumcreek.blogspot.com.au

Facebook: www.facebook.com/pages/Jill-Weatherhead-Garden-Design/129515470490290

Instagram : www.instagram.com/jill_weatherhead